‘Colossal’ central bank buying drives gold demand to decade high

A gold smelter in Sydney, Australia. Central bank purchases of gold hit 417 tonnes in the final three months of 2022, roughly 12 times higher than the same quarter in 2021Harry Dempsey @Financial Times

Fallout from US sanctions on Russia helped fuel 18 per cent leap in purchases last year

Demand for gold surged to its highest in more than a decade in 2022, fuelled by “colossal” central bank purchases that underscored the safe haven asset’s appeal during times of geopolitical upheaval.

Annual gold demand increased 18 per cent last year to 4,741 tonnes, the largest amount since 2011, driven by a 55-year high in central bank purchases, according to the World Gold Council, an industry-backed group.

Central banks hoovered up gold at a historic rate in the second half of the year, a move many analysts attribute to a desire to diversify reserves away from the dollar after the US froze Russia’s reserves denominated in the currency as part of its sanctions against Moscow. Retail investors also piled into the yellow metal in a bid to protect themselves from high inflation.

Central bank purchases of gold hit 417 tonnes in the final three months of the year, roughly 12 times higher than the same quarter a year ago. It took the annual total to more than double of the previous year at 1,136 tonnes.

Krishan Gopaul, senior analyst at the WGC, said “colossal” central bank buying is a “huge positive for the gold market”, even as the industry group predicted that it would be tough to match last year’s purchases because of a slow down in total reserve growth.

“Since 2010 central banks have been net purchasers of gold following two decades of net sales. What we have seen recently in this environment is central banks have accelerated their purchases to a multi-decade high,” he said. He added that a lack of “counterparty risk” was a key attraction of the metal for central banks, compared with currencies under the control of foreign governments.

![]()

Only about a quarter of the fourth-quarter central bank purchases were reported to the IMF. Reported purchases in 2022 were led by Turkey taking in almost 400 tonnes, China, which reported buying 62 tonnes in November and December, and Middle Eastern nations.

Gold industry analysts widely believe the remainder is accounted for by central banks and government agencies in China, Russia and the Middle East, which can include sovereign wealth funds.

James Steel, a veteran precious metals analyst at HSBC, said that “portfolio diversification is the main reason” for US dollar-laden central banks buying gold. He adds that “a key reason for choosing gold is that central banks are limited in what assets they can hold, and they may be reluctant to commit to other currencies”.

Demand among retail investors for bar and coins also jumped to a nine-year high in 2022 above 1,200 tonnes with strong demand in Europe, Turkey and the Middle East offsetting weakness in China where buyers were housebound by Covid lockdowns.

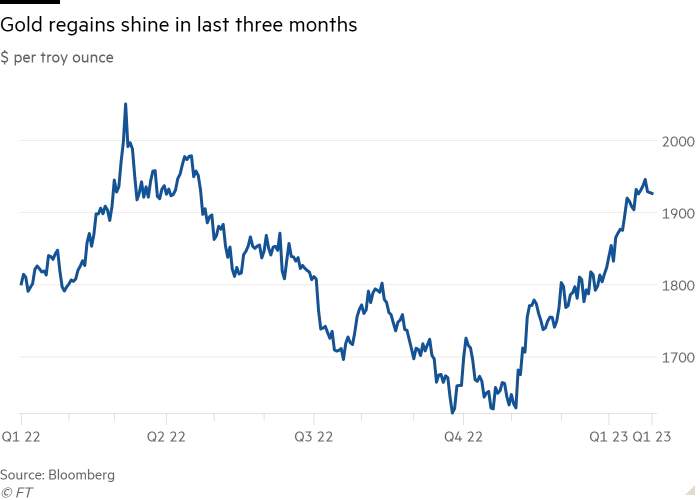

Gold prices slid from a record high last March above $2,000 to just above $1,600 per troy ounce in November as rising interest rates led to outflows from gold-backed exchange traded funds equivalent to $3bn over the year. Gold produces no yield, dulling its appeal to investors when interest rates on low-risk bonds climb.

However, demand from central banks and retail investors helped prevent the yellow

In those three months, gold has jumped almost a fifth to $1,928 per troy ounce — its highest level in nine months — helped by the US Federal Reserve signalling that it would slow down the pace of rate hikes.

The WGC expects a revival in gold demand from institutional investors this year as interest rates in main economies approach their peak, while falling inflation could damp demand for bars and coins.

As a result of exceptional central bank buying and an expected return of inflows for gold-backed ETFs, UBS raised its year-end target for the precious metal to $2,100 per troy ounce, up from $1,850 previously.